There are many aspects to the desperation which has driven the Syrian

refugees to this self-organised protest. Many of them are on hunger

strike. One common bond is the fear of being trapped in Greece with no

money and no support. Without money to pay your way out of Greece

clandestinely you face a frightening future.

Many of the Syrians who make it to Greece have some money; some have

much. In many respects those in Syntagma square, are more privileged

than the millions of Syrians living in the camps in Turkey or Jordan. Of

the 11 million Syrians refugees today (including those internally

displaced within the country as well as outside the borders) only 4%

make it to Europe.

We were told many stories in the Square of people selling homes, cars

and businesses to pay for the escape from Syria. But as a consequence

of there being no provision for safe travel to the EU, the Syrians as

with all refugees without papers, are forced to pay for clandestine

routes into Greece. It is very expensive.

We discovered that in many cases the money was focused on one person

in the household group. Usually the father/husband, although we also met

some mothers who were travelling alone with their children. The plan is

for this person to find a safe place in Europe where they would be able

to bring the rest of their family and live together again. This appears

to be one of the most important criteria for choosing particular

destination countries such as Sweden, Norway and Germany. The other was

joining relatives and friends already settled in Europe which is

particularly the case for Sweden which has a relatively large Syrian

population. No one we met wanted to stay in Greece.

“They don’t want us in Greece. But they won’t let us leave. We

are in a place worse than a prison. We can’t work, we have no housing,

no medical care, schools for our kids and we are running out of money.”

“They don’t want us in Greece. But they won’t let us leave. We

are in a place worse than a prison. We can’t work, we have no housing,

no medical care, schools for our kids and we are running out of money.”

(

Bassel, 28 years, finance manager)

“I am trying to join my brothers who are now in Germany. They are waiting for me. I don’t want to be here.”

(

Halil, 18 years, high school student)

“I have one brother in London and one brother in Manchester and I

want to be with them. I have tried to see if the British embassy [in

Athens] can help me. But I am always turned away by the security guards.

I can’t speak to anyone there.”

(

Nizar, 17 years, high school student)

“I am a barber from Aleppo. I am 28 years old. My wife and my 2

daughters are still in Syria. My youngest daughter, Maria, was born last

week and I have only seen her in this photo [which he shows]. I left

Syria five weeks ago to find a safe country for my family. This is my

purpose. This is why I want to go Norway or Sweden because there I can

get my family. In Greece, never.

(

Fathi, 28 years )

“I don’t think you will find any of us on this protest who wants

to stay in Greece. But this is the only way for us to get to Europe. We

don’t want asylum here. There is nothing for us here. Nothing. They just

want our money.”

(

Nour, 23, journalism student)

“It took me three tries to get from Izmir to Chios in October

this year. The first 2 times we were caught by the Greek coastguard who

took us back and gave us to the Turkish coastguard. It cost 3,000

euros.”

(

Suzy, 22 , English Literature student)

“Every attempt I make to leave Greece costs money. Mainly to the

smugglers who try to get us across borders [without papers]. But how

long will my money last? I am paying 100 euros a month to live in a 2

room studio with 9 others. It is expensive because we can’t rent houses

and the government here only provides for a few families with children.”

(

Ammar, 19 , first year electronics student)

“I knew from my friends who came before that Greece would be a

hard place. But it was only when I was put in the Samos camp [after

arriving from Turkey in a small plastic boat] that I saw how much we are

hated here. It is not human.”

(

Natalia , 36, teacher)

“Once we start on this journey, we have to pay for every step of

the way. I paid $ (US) 2,000 to come in a rubber boat to Mytilene. There

were 35 of us. I was terrified. We travelled at night. The waves were

coming in all the time. There were young children with us. I was put in

the camp and after 7 days left for Athens. I have been here 4 weeks

now.“

“Once we start on this journey, we have to pay for every step of

the way. I paid $ (US) 2,000 to come in a rubber boat to Mytilene. There

were 35 of us. I was terrified. We travelled at night. The waves were

coming in all the time. There were young children with us. I was put in

the camp and after 7 days left for Athens. I have been here 4 weeks

now.“

(

Mohammed, 26, marketing student)

“For me it was a jet ski from Bodrum with 2 friends. It was night

time and we were taken to Kos. But as it got light and we walked around

we found that we had been left on a small island, completely empty. No

houses, no people. After about 5 hours a Greek coastguard boat came and

took us to Kos. “

(

Nour,23)

“I have been unlucky. I paid 3,000 euros to go on a yacht from

Fethiye in Turkey to Italy. The boat was good and there were just 8 of

us. But about 20km from the Italian coast we ran out of fuel. We were

able to contact the coastguard in Italy but they told us we were too far

from the coast and had to come nearer before they would come out to

rescue us. But we couldn’t move. Then a ship came but said they wouldn’t

take us but they had radioed another ship that would come and pick us

up. It was a Russian ship going to Palestine. They took us and were

sorry that they couldn’t take us to Italy so we were dropped off in

Rhodes. I wanted to keep out of Greece and now here I am. Trapped. In

the six weeks I have been here I have tried to get out, 2 times I got

into Macedonia but then caught and returned, one time to Albania and the

same, and also Igoumenitsa . My money is going.”

(

Bassel, 28)

“I paid 1,500 euros to come in a small boat to a Greek island

(Samos). We were promised that it would be safe. But they filled the

boats with people. I had to leave all my luggage on the beach in Turkey

as the smugglers wanted all the space for people. I was very

frightened.”

(

Zeinah, 25, postgraduate law student)

“I am wearing all the clothes I own now. The Greek coastguards

made us throw our bags into the sea. I was warned this could happen so I

left all my papers (about his qualifications and education) with my

brother in Turkey and he will send them when I am safe. Most are not so

lucky and have lost very important documents.”

(

Ammar, 26, medical student)

Because there is no safe passage to Europe, the Mediterranean area,

including the Aegean, has become the most dangerous border area in the

world “between countries that are not at war with each other. The risks

of dying while crossing this border are close to 2%. Crossing the

Mediterranean is more lethal than crossing the Rio Grande from Mexico to

the USA, the Indian Ocean from Indonesia to Australia, or the Gulf of

Aden from the Horn of Africa to the Arabian Peninsula”(Philippe Fargues

and Sara Bonfanti, Migration Policy Centre, EUI October 2014). Even when

you succeed in crossing the sea the dangers to life continue.

Tragically, one of the Syrians who had been at the Syntagma protest,

Ayman Ghazal, died last week whilst trying to cross the border between

Albania and Greece.

A large number of those we spoke with were students of whom around

30% were young women. The majority was at university and a small number

were still in high school. Very few of them had finished their studies

and were desperate to complete their courses. Some of our conversations

were in Arabic but many were in English as so many of the students were

fluent speakers. Ranging from marketing, law, medicine, journalism,

English literature, IT, electrical engineering, teaching, these students

spoke passionately about their education and their need to find

somewhere to complete their courses.

Despite their circumstances the students – indeed all those we met –

were confident about their abilities to re-build their lives in Europe.

They just wanted to be given a chance to move freely with rights to work

and study.

But without exception every Syrian we spoke with had suffered pain

and fear. In the midst of stories being exchanged we got to hear how

many had been in Syrian jails and police stations. There was the final

year medical student whose strapped hand and wrist was a legacy to being

suspended by his wrists while in a police cell. Many had lost close

relatives and friends either killed or wounded. Constant fear was their

companion in Syria. So was hurt, as they saw much loved cities and towns

pulverized and cleaned of their people. And on top, the daily

uncertainty, never knowing when or where the violence would strike next.

“When you come to a country in a crowded rubber boat which has

cost you 2,000 euros to make a four hour journey, you know that you are

heading for trouble. But I also thought that in Europe which we are told

is so advanced and civilized that our wounds and fears we carried with

us would mean that we would be helped. But we have been treated worse

than animals [in the Detention Centres and Greek police cells]. Nobody

asked me why I left Syria, or what I had experienced. Do they think we

want to come to Greece for this? I never wanted to leave my home. I love

Damascus. Now I may never be able to return.”

(

Ranim, 31, accountant)

“Look at this [he plays a video on his phone]. This is Raqqa 2

days ago where bombing by Assad’s planes martyred over 200 people and

injured many more. Look at those streets with smashed people. This I

lived with. The planes bomb and then return 15 minutes later to bomb the

people who go out to save people from the first raid. And now the

Americans are bombing the town.

My father was born in Raqqa so on my ID it says I am from Raqqa

although we live in a small village 15kms from the town. But because my

ID says Raqqa my life is hell in Syria. Because Raqqa is controlled by

ISIS it means that the government sees all people from there as ISIS

supporters.”

(

Firas 29, mechanic)

“Until this summer I had a good job as a finance manager for a

big company. As a third generation Palestinian I grew up in a camp near

to the city but that was badly damaged three years ago so we moved

nearer to the centre. I drive to work and have to pass through many

military checkpoints. At one of the checks, just because I was

Palestinian, I was told to get out the car and to walk for fifteen

minutes around a square which was known for its snipers. I walked

reciting the Koran and thinking of my two young sons; waiting to be

shot. This happened to me three times this year. After the last time I

and my wife decided that we should leave, me going first with my family

to follow. I last saw them 6 weeks ago.”

(

Bassel, 28)

“It became impossible for me to stay in Syria. I applied and got a

very senior appointment in a hospital based in Qatar, but I couldn’t

get permission from the government there to work in the hospital. I am a

specialist neurologist. “

(

Moussa, 36, doctor)

“For tn years I was a journalist in Damascus and managed to avoid

the eye of the government. Then I wrote one article that was mildly

critical of Assad and I ended up in police cells for one year. I left

immediately I was released. My brother is a journalist for an Arab paper

and is in London. I want to join him.”

(

Ahmed 43, journalist)

Many of the refugees were astonished by their treatment both from the

Greek state and its agencies and from the way they were being ripped

off as they tried to both survive and escape from Greece. Its neglect,

its casual cruelties, the way in which they are left in limbo with no

control over their lives as the Greek state processes them is totally

devoid of humanity.

It was the hope of many we spoke with that they could succeed in

getting the Greek state to either reach a national solution or even

better force an EU resolution which would give them refugee status with

the right to travel, work and live anywhere within the EU. Given this

strategy it is not surprising that many on the protest wanted to know

about the government, its power within the EU, and why so many of its

refugee policies were focused on repression and exclusion and not on

human welfare.

But even after a few days of the protest there is a growing sense

amongst the protesters that the Greek government is not up to much and

not prepared to do anything positive for them.

“My first time in a police cell was in Athens. I never thought this would happen to me.”

(

Nizar, 17)

“I don’t know who came over from the Parliament yesterday but he

told us that we could not achieve our demands. He said that there was

little they could do but he hoped that some houses would be given to

families with children. We were disappointed but not surprised. They

will try and divide us I think, giving some things but only to a small

number. But if we don’t keep together we are nothing.”

“I don’t know who came over from the Parliament yesterday but he

told us that we could not achieve our demands. He said that there was

little they could do but he hoped that some houses would be given to

families with children. We were disappointed but not surprised. They

will try and divide us I think, giving some things but only to a small

number. But if we don’t keep together we are nothing.”

(

Ammar, 26, medical student)

“I can see now many similarities between the Greek and Syrian

systems. It is a common Arab experience. But I think the Greek

government is worse. Nothing works, nothing happens that is good for the

people.”

(

Zeinah, 25, postgraduate law student)

“Is it because most of us are Muslims that we are treated like

this? I never thought about this before but I am beginning to think that

we are being punished because we are Moslem.”

(

Ammar,26)

The reaction of his friend, another university student was amazement:

“This cannot be true. Islam is an open religion and is about

living together in peace and within a framework which is not too tight

and not too loose. There is nothing to fear from Islam.”

(

Mohammed, 26, marketing student)

“I am always thinking as we sit here all day. I look at the

people passing on the street. I think that if they are Greek that they

will have papers that allow them to travel and to move. What is

different about them from me? Why can they have this freedom and not me?

I think my life might be better if I was a dog. At least then I can get

a passport to travel in Europe. “

(

Ammar, 26 years, final year medical student)

It is the character of some protests at least, especially those which

give time to the activists to know one another and to talk that there

are opportunities to learn and gain greater understanding. This is

clearly happening for many in Syntagma. A clear example occurred around 6

days into the protest (26 Nov 2014) when a leaflet from the Ministry of

Interior was distributed to the activists. It was in Greek and English

with a few lines of incomprehensible Arabic scrawled along the bottom.

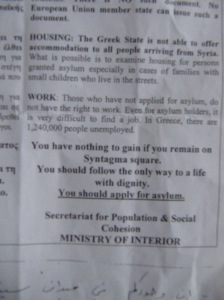

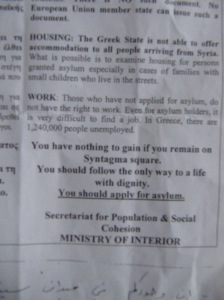

This was the leaflet’s message set out in bold type:

You have nothing to gain if you remain on

Syntagma square.

You should follow the only way to a life

With dignity.

You should apply for asylum.

“I can’t understand. In this paper the government tells us “The

Greek State is not able to offer accommodation to all the people coming

from Syria. What is possible is to examine housing for persons granted

asylum especially in cases of families with small children who live in

the streets”. Then it says:”WORK: Those who have not applied for asylum,

do not have the right to work. Even for asylum holders, it is very

difficult to find a job. In Greece there are 1,240,000 people

unemployed.” We are not crazy. We don’t want asylum in Greece.”

(

Bana 26, journalism student)

“I had not realized how bad it was in Greece until the women

cleaners stopped during their demonstration. The poverty here is very

bad. Even if you get a job the wages are very low. But it is the poor

people here who help us the most. The women cleaners felt our pain.”

(

Zeinah, 25, postgraduate law student)

“It says that if get asylum we “can also visit other European

countries for three months twice a year.” This is no good for me. I want

to be with my brothers in Germany. Not here.”

(

Halil, 18 years, high school student)

“The more I hear the more I am determined not to apply for asylum

in Greece. I have met refugees from Algeria who have waited for 7 years

to get a blue passport [asylum]. How can we wait like this? “

(

Ranim, 31, accountant)

“

If I get asylum it will be impossible for me to ever return to

Syria. I don’t want to do this. I want to get to a country where I can

stay but never give up my right to return.”

(

Nour,23)

“The parliament members are very sleepy and I am really surprised

at the way that they are managing the issues in this country. They are

useless and have no power to speak up towards other European countries;

it’s really sad to have such an attitude from a European country

member.”

(

Bassel, 28)

There is enormous dignity in this protest. It is well run, the area

occupied is regularly cleaned; they have a pile of donated clothes which

they manage as well their own valuable skills. So the doctors and

medical students amongst them check regularly on those who are suffering

as the hunger strike deepens and there are toys and games for the young

children. Together the hundreds of Syrians in the square have created a

sense of purpose and solidarity. They remain determined. They have so

little to lose. They are not being led from the outside but are self

organized with a lot jokes and laughter and much talking. It is an easy

place to be and the refugees are thirsty to discuss and share their

lives and struggles with all those who care to spend time with them.

As we write the protest in Syntagma continues into its 20th day. One

of the friends we made sent us the following message this morning

; “the

weather is getting worse and the children and women still sleeping in

the square. It’s a big shame on them. We are still here and we stay in

the square since we have no choice. We have to fight for our rights”.

(Bassel, 28)

We live in a world where innocent victims of atrocities and violence

are caught up in situations well beyond their control and yet when they

seek refuge they are further violated and humiliated. Then in order to

gain some modest but fundamental rights, they have to fight and

struggle. In the name of our common humanity it is intolerable to accept

a world which so mercilessly creates millions of refugees and then sets

out to punish them further. This is not a struggle which can be carried

alone by the refugees.

Are we going to stand back and watch in silence?

Source:

http://samoschronicles.wordpress.com/2014/12/09/in-syntagma-square-syrian-refugees-fight-back/